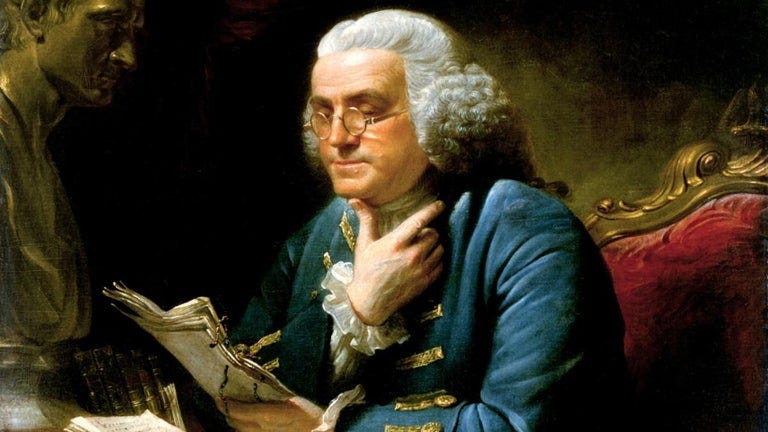

As I stated last time, I’m reading HW Brand’s “The First American: The Life and Times of Benjamin Franklin.” It’s been a great read and a highly recommend it.

My last post was focused on Franklin’s “four commandments and thirteen cardinal virtues.” You can read that list here:

This post is on a similar topic — a work intended to be called “The Art of Virtue” — which Franklin “ruminated on for nearly 30 years” but never completed. I guess he was busy with other things? Go figure.

Regardless, I feel the rough framework of this intended book worthy of sharing here.

Many people lead bad lives that would gladly lead good ones, but know not how to make the change. They have frequently resolved and endeavoured it; but in vain, because their endeavours have not been properly conducted. To exhort people to be good, to be just, to be temperate, &tc. without showing them how they shall become so, seems like the ineffectual charity mentioned by the Apostle, which consisted in saying to the hungry, the cold, and the naked, be ye fed, be ye warmed, be ye clothed, without showing them how they should get food, fire, or clothing.

Most people naturally had some virtues, but none naturally had all the virtues. To secure those bestowed by nature, and to acquire those wanting, was the subject of an art.

It is as properly an art as painting, navigation, or architecture. If a man would become a painter, navigator, or architect, it is not enough that he is advised to be one, that he is convinced by the arguments of his adviser that it would be for his advantage to be one, and that he resolves to be one; but he must also be taught the principles of the art, be shewn all the methods of working, and how to acquire the habits of using properly all the instruments. And thus regularly and gradually he arrives by practice at some perfection in the art.

Franklin distinguished virtue from religion. Christians were exhorted to have faith in Christ as the means to achieving virtue; having spent his life among Christians, Franklin was by no means inclined to deny the possibility of this path to virtue. But that same life among Christians disinclined him to assert its inevitability. Besides, Christians- either nominal or practicing— were not the whole world.

All men cannot have faith in Christ; and many have it in so weak a degree that it does not produce the effect. Our Art of Virtue may therefore be of great service to those who have not faith, and come in aid of the weak faith of others. Such as are naturally well-disposed, and have been carefully educated, so that good habits have been early established, and bad ones prevented, have less need of this art; but all may be more or less benefited by it. It is, in short, to be adapted for universal use.

There’s a ton of great things worth parsing out in the above passages, however, drilling it down to one central idea, my read is that virtue is an act of everyday effort.

You cannot force someone to make virtuous decisions. You have to show them that virtue naturally benefits them and helps them achieve their goals and wants and needs.

It reminds me of a passage from William Green’s book “Richer, Wiser, Happier.” In it, Green relates a story from Tom Gayner, CEO of Markel, about the most important lesson he’s learned from Warren Buffett.

"What Buffett stressed," Gayner told me, "is that it's so important to be truthful because, if you engage in untruthfulness, ultimately you will lie to yourself. And that's where you really get in trouble. So, it's a habit and a discipline that, in addition to being the right thing to do, just works."

Gayner adds: "Sometimes, people can build great careers and enjoy great successes for a period of time through bluster and bullying and intimidation and slipperiness. But that always comes unraveled... The people you find that just keep being successful year after year after year... are people of deep integrity."

The last lesson from Franklin’s “Art of Virtue” worth learning is that religion does not necessarily make someone more virtuous. Although it can be an excellent springboard for folks to make good decisions that are mutually beneficial for everyone, everyone reading this can certainly list countless examples of the reverse being true in our own personal lives as well.

It is speculated by historians Franklin did not finish this project because he felt a work about perfection should be perfect. Because he never found the perfect medium or prose, he never published these ideas and principles.

I share the same fear each time I post on this Substack. I hope folks don’t think because I’ve shared these ideas on virtue I must assume I am virtuous or perfect.

I do not and am not.

But it’s worth it to try, right?

That’s all for now,

Tyler